Challenging the meritocratic ideology in engineering education

Note: This blog post was written before the recent Supreme Court rulings striking down Affirmative Action. While I don’t comment on these rulings directly, the discussion of merit and meritocracy in this blog post intersects with the broader discourse surrounding these rulings.

When I was in high school, grade point average (GPA) and standardized tests scores were the markers of future success. My high school ranked students based on GPA, and colleges used GPA and SAT scores (along with other factors like extracurriculars) to determine which students to admit. Thus, for my classmates and I, the surest road to future success was to make our GPAs and test scores as high as possible. Individually, I believed that my high scores represented my aptitude and hard work and thus demonstrated my worthiness to attend a selective college.

My high school experience reflected a cultural belief in meritocracy, or the idea that personal and career successes are (or should be) distributed across individuals primarily as rewards for individual talent, training, and hard work (i.e., “merit”). As a high school student, my “merit” was represented by my GPA and test scores, and I competed against other students based on my merit for admission to selective colleges. It’s worth noting that the person who originally coined the term “meritocracy,” Michael Young in The Rise of the Meritocracy (1958), meant for his imagined system of competitive, merit-based advancement to be a satirical social critique. Nevertheless, within American culture, there is a certain seductive logic to the meritocratic ideology: work hard and you will get what you deserve. Pull yourself up by your bootstraps. If you fail, then you must not have worked hard enough. This ideology is not limited just to college admissions; it pervades much of the discourse in America around social advancement and access to opportunities.

Do Americans actually live in a meritocracy? Short answer – no. Meritocratic systems are defined by two fundamental criteria: 1) individuals must have equitable and fair access to opportunities and rewards (i.e., equality of opportunity), and 2) opportunities and rewards must be distributed across individuals through fair competition. Neither of these criteria bears scrutiny. For example, in my high school experience, merit was conflated with a high GPA. The best way to achieve a high GPA was to take as many Advanced Placement (A.P.) courses as possible, since A.P. classes contributed 6.0 points to our GPAs rather than the 4.0 points conveyed by standard courses. Access to such courses was not equitable or fair. My public high school, which was well funded and had excellent teachers, offered a wide range of A.P. courses that were not available at other local high schools. My high school also allowed me to take further math courses at the local public college for A.P. credit. Within A.P. courses, competition was not fair either. I benefited from an exceptionally supportive and financially secure home environment that allowed me to focus entirely on my studies starting all the way back in preschool. While my GPA did represent my individual aptitude and hard work, it also represented my systemic advantages compared to my peers against whom I was competing for college admission.

Even though the fundamental assumptions of meritocracy (equality of opportunity and fair competition) do not hold in reality, there is a strong cultural belief in America that social advancement should be meritocratic. Prior research has suggested that belief in meritocracy is especially strong among engineers, in part because the meritocratic ideology is deeply embedded in engineering academic and professional cultures (Cech, 2013). For example, “weed out” classes are common in engineering education; these classes are so difficult that failure is common, with the goal of reducing the crop of aspiring engineers to only “the best and the brightest.” Students internalize these messages: succeed in your engineering classes, and you have earned the right to become an engineer. Your success depends on how hard you work and your ability to endure hardship. Engineering is “harder” than other majors, meaning that engineers are more deserving of societal rewards such as well-paying jobs. Flunk out of engineering, and you must not have been good enough. Not only are these messages not true – your worth as an engineer isn’t predicated on your ability to endure hardship – they also reflect a White and hyper-masculine version of engineering that is toxic to minoritized students.

The prevalence of the meritocratic ideology within engineering culture creates several problems. First and foremost, the conflation of “merit” with overwork and high test scores is severely damaging to engineering students’ mental health. As an undergraduate engineering student, I developed chronic anxiety because my academic standing was so strongly dependent on my exam performance. I wasn’t alone: research shows that engineering students experience unusually high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (Jensen & Cross, 2021). In addition, the meritocratic ideology contributes to a “culture of disengagement” in engineering education because it leads engineering students to view widespread social stratification based on race and gender to be the result of fair meritocratic processes rather than structural oppression (Cech, 2014). Lastly, “merit” is subjective, and notions of engineering merit have traditionally been gendered (masculine) and raced (White). Thus, as discussed in Kaylla Cantilina and I’s 2022 ASEE ECSJ paper, the meritocratic ideology in engineering can ascribe additional merit to White men compared to equally qualified women of color, thus contributing to the systemic exclusion of women of color from engineering spaces.

In my current career as an instructor and researcher, I strive to create the engineering academic environments that I wish I had encountered as an engineering student. My goals include 1) challenging the meritocratic ideology in engineering and 2) understanding how my experiences as an engineering student compare to (and differ from) the experiences of current engineering students. For example, at the University of Michigan, I worked with Drs. Shanna Daly, Steve Skerlos, and Sara Hoffman to develop pedagogies to counter meritocratic mindsets in engineering students. Part of this effort involved investigating how junior- and senior-level engineering students related to the meritocratic ideology – particularly related to engineering career advancement – and the extent to which these students held meritocratic beliefs. We identified two key findings, described in our 2022 ASEE ERM paper:

- Students felt that getting a job in engineering was as much about personal connections as it was about individual merit. Several students claimed engineering was “nepotistic.”

- Students were split as to whether engineering career advancement should be meritocratic. Students consistently agreed that engineers needed the right competencies for their jobs but provided several reasons why “merit” shouldn’t be the sole consideration in hiring.

As instructors, we found these findings to be highly encouraging: our participants discussed complex perspectives on the meritocratic ideology in engineering and there was ample room to push student mindsets in more equitable directions. Building on these findings, instructors could challenge students to think about how merit is subjective and how traditional metrics of merit in engineering education – such as GPA and technical knowledge – reflect only a subset of the knowledge that engineers need to perform their jobs effectively. Instructors could also build students’ “power consciousness” – i.e., their ability to recognize their individual social power and resulting privileges and opportunities – and use this discussion to emphasize engineers’ responsibilities to society.

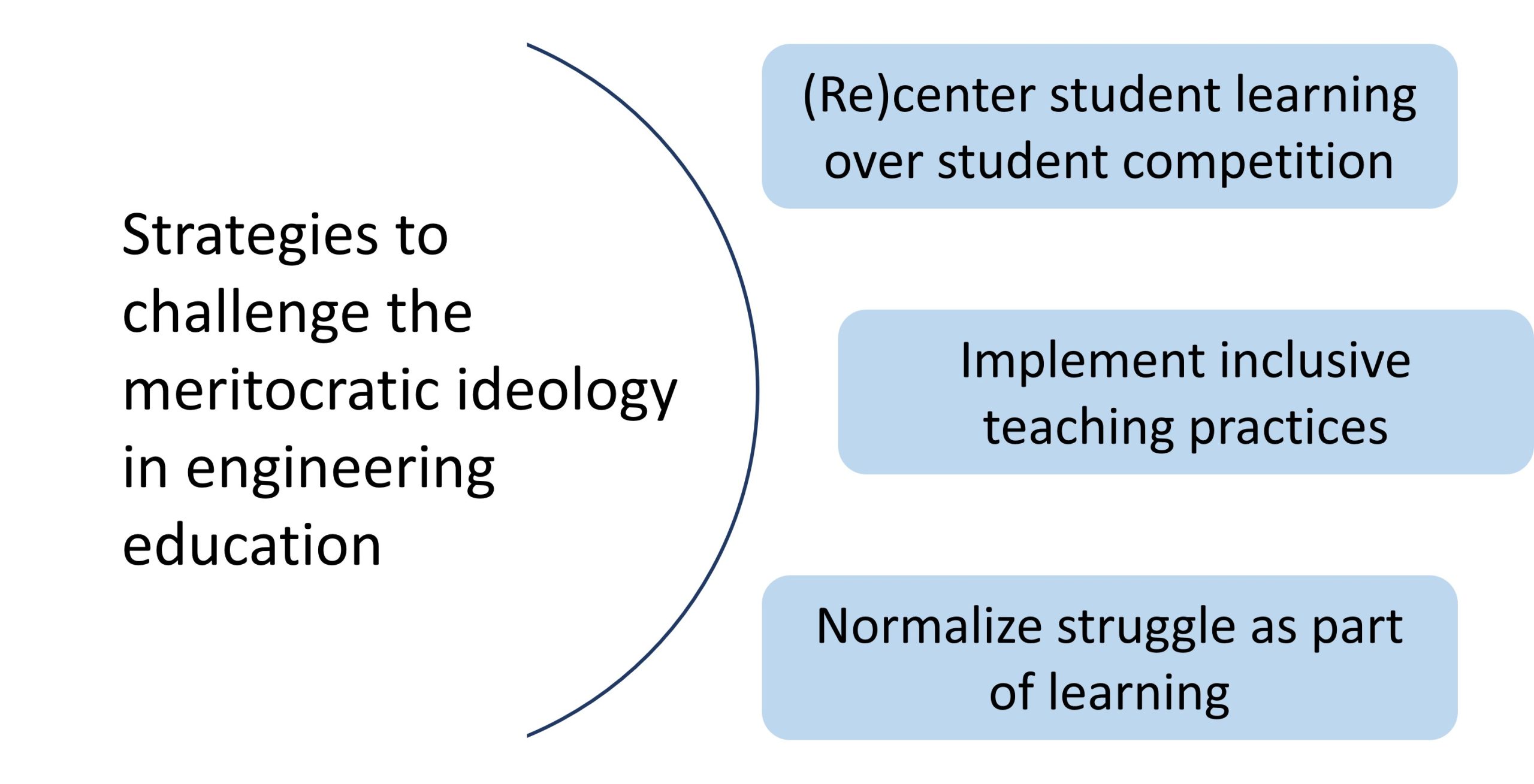

While these instructional strategies may change individual minds, part of the problem with the meritocratic ideology in engineering is that it is cultural, meaning that this ideology is deeply embedded in how we teach and practice engineering. Cultural problems require us to change how we teach, not just what we teach. A good first step is to (re)center student learning as the goal of engineering education. “Weed out” classes thrive on brutally difficult exams where failure is common and grades are eventually curved into As, Bs, Cs and Ds based on the overall performance of the class. Curved exams don’t measure actual student performance; rather, they create arbitrary competition by normalizing students’ scores against their peers. What if, instead, we made curves obsolete by consistently designing our assessments to be well aligned with our course content and learning goals? In a well-designed course, students should be able to succeed without a curve.

Strategies to challenge the meritocratic ideology in engineering education

Another way to address the meritocratic ideology in engineering is through inclusive teaching. Inclusive instructors celebrate difference in their classrooms, foster a culture of care, and provide multiple ways for students to demonstrate their achievement (i.e., their “merit”) beyond just exams. I teach design courses and thus favor open-ended design projects, but just about any assignment that provides students with an opportunity to connect their engineering learning either to themselves or to the real world would work. The goal is to empower students to show what they know in authentic ways – rather than by conforming to an arbitrary standard that privileges White men – while supporting their holistic (not just academic) growth. The University of Michigan’s Center for Research on Learning and Teaching in Engineering has curated many great resources on inclusive teaching strategies. These resources can be found at: https://crlte.engin.umich.edu/inclusive-teaching-tools/

We can also challenge the meritocratic ideology in engineering by normalizing struggle as a normal and healthy part of learning, rather than a reflection on our worth as engineers. Everyone struggles in engineering – from course content, from balancing coursework, from adjusting to college, from simply navigating life. However, in engineering we rarely talk about our struggles, with the result being that many women and students of color in engineering view their struggles as individual and indicative that they don’t belong in engineering. One way that instructors can normalize struggle is through an Ecological Belonging Intervention developed by Drs. Linda DeAngelo, Allison Godwin and colleagues (described in this ASEE paper); this intervention is designed to contextualize students’ struggles and reinforce the idea that anyone can be an engineer as long as they are dedicated to their learning and constant improvement. Ultimately, there is no one way to be an engineer, just as there is no single definition of “merit” that fully captures all the skills or capabilities that engineers need to address modern societal challenges.

References

Cech, E. A. (2013). The (Mis)Framing of Social Justice: Why Ideologies of Depoliticization and Meritocracy Hinder Engineers’ Ability to Think About Social Injustices. In J. Lucena (Ed.), Engineering Education for Social Justice: Critical Explorations and Opportunities (pp. 67–84). Springer.

Cech, E. A. (2014). Culture of disengagement in engineering education? Science, Technology, & Human Values, 39(1), 42–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243913504305

Jensen, K. J., & Cross, K. J. (2021). Engineering stress culture: Relationships among mental health, engineering identity, and sense of inclusion. Journal of Engineering Education, 110(2), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20391

About the Author

Robert P. Loweth (he/him) is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the School of Engineering Education at Purdue University. His research explores how engineering students and practitioners engage stakeholders in their engineering projects, reflect on their social identities, and consider the broader societal contexts of their engineering work. The goals of his research are 1) to develop tools and pedagogies that support engineers in achieving the positive societal changes that they envision and 2) to address systems of oppression that exist within and are reproduced by engineering education and work environments. He earned his B.S. in Engineering Sciences from Yale University, with a double major in East Asian Studies, and earned his Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Michigan. He also holds a Graduate Certificate in Chinese and American Studies, jointly awarded by Johns Hopkins University and Nanjing University in China.

Robert P. Loweth (he/him) is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the School of Engineering Education at Purdue University. His research explores how engineering students and practitioners engage stakeholders in their engineering projects, reflect on their social identities, and consider the broader societal contexts of their engineering work. The goals of his research are 1) to develop tools and pedagogies that support engineers in achieving the positive societal changes that they envision and 2) to address systems of oppression that exist within and are reproduced by engineering education and work environments. He earned his B.S. in Engineering Sciences from Yale University, with a double major in East Asian Studies, and earned his Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Michigan. He also holds a Graduate Certificate in Chinese and American Studies, jointly awarded by Johns Hopkins University and Nanjing University in China.

Connect with our guest blogger

Do you want to become a guest blogger?

CDEI Guest Blog highlight future events, describe best practices, or share calls to action by CDEI members. We invite you to propose posts that share brief research highlights, reports of impactful initiatives, critical thought pieces, and resources you find useful. We especially encourage emerging scholars to share their work. If you are interested in sharing a blog or resource post, you may submit your proposal here. All posts are screened and edited.