When Anti-Blackness is Endemic to Society, Equitable Teaching Can Get You in (Serious) Trouble

by Ɔbenfo James Holly, Jr.

Trouble

On March 1, 2020, John Lewis spoke on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma as part of an event to commemorate Bloody Sunday. In his remarks he provided a call to action: “Get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America.” Since his death the phrase ‘good trouble’ has become a common refrain, yet it has been reduced to saying provocative and perhaps controversial things rather than disrupting power relations to elevate the marginalized in our society. As engineering educators we have to determine for ourselves whether we are really willing to get into “good trouble” to see true education actualized.

I learned in adulthood while talking to my favorite teacher, Ms. Pagan who was my first- and second-grade teacher at Sherrard Elementary, a school now closed and demolished. She told me she was always in trouble with her peers and school administrators. I could share some of the consequences she suffered but that wouldn’t be as helpful as sharing her resolve: she was determined to provide educational excellence to her students by any means necessary. Generally a phrase inferring the possibility of violence, for Ms. Pagan this ethos meant countering the violence levied against us as her students. She endured many troubles so that the troubles resulting from ignorance would be mitigated.

For those willing to get into trouble for the sake of improving education, keep reading…

As an adolescent I realized something about myself: I got into trouble a lot, and I had the worst timing for when I’d be grounded–a restrictive punishment that meant loss of social privileges. I never enjoyed any of the forms of discipline I experienced, but they didn’t deter me from doing certain things that I did enjoy even when I knew I would suffer painful consequences as a result. My mother was stressed many days and nights as she tried to understand why I knowingly disobeyed her, but she focused on what I would lose whereas I was focused on what I would gain (of course, I often miscalculated!). As I have spent years studying the experiences of Black people in the United States, from the Maafa to present-day, I noticed a trend of Black people risking everything, to gain…everything. Already in precarious circumstances they did not act out of nihilism; on the contrary, they were full of optimism! I read about enslaved Africans that learned to read (and write); enslaved Black Americans that broke free; free Negroes that invaded restricted spaces; second-class citizens that filed (and won) court cases. They behaved in a manner that subverted the social structure, in order to attain liberation, often for themselves and others. Our contemporary social and material conditions are much different than during the eras I have studied even though those periods of time aren’t long ago, nevertheless, we are still engaged in intellectual warfare regarding who can be knowers and what knowledge is worth knowing.

Fugitive pedagogy

Fugitive pedagogy

Fortunately, there exists a pedagogical framework that we engineering educators can employ to prepare engineering students to intentionally and justly impact the distribution of wealth, power, and privilege in society. Fugitive pedagogy fits the bill. Jarvis Givens studied the ways Black teachers and students challenged white supremacy, which led to his conception of fugitive pedagogy. The language of fugitivity is not intended to suggest seeking trouble for the sake of trouble nor advocating lawlessness, rather it draws on the ways African-descended people challenged the “chattel principle,” the very laws and logics condemning them to a subgenre of the human species…” (p. 10). Modern book bans have roots in past anti-literacy laws. Fugitivity is about subverting white supremacist educational structures to properly educate all people. Though I am specifically talking about the instructional philosophies and practices of Black educators that primarily taught Black youth, I framed it as equitable teaching for two reasons: i) people tend to think the educational strategies Black teachers use are only useful for Black students, and ii) equity is essentially the outcome of these strategies that have been cultivated through attention to the needs of a particular racial demographic.

One asset of fugitive pedagogy is that it isn’t prescriptive, but it is value-centered and action-oriented. Black educators have embodied it in numerous ways. I share three of the many methods fugitive pedagogues utilized that I believe can be immediately adopted in engineering education:

- Infused lessons with Black perspectives

- Subtly included texts by Black authors

- Created extracurricular activities that reinforced a sense of identity and purpose among their students

James Holly, Jr. talking with students in his Mechanical Engineering and Racial Justice course

If these actions appear simplistic or perhaps not very radical, that is intentional. My goal is to invite others to engage in this work. Though I caution against underestimating the power of these epistemic practices. Epistemological resilience, a component of epistemic oppression, is essentially the ability of dominant epistemic resources to remain the same despite compelling challenges because they are viewed as reliable to the majority of knowers and thus are not seen as needing to change. An example of this is the relatively stable curricula governing undergraduate engineering education. The rhetoric within engineering education has shifted to more advocacy for educational equity but how can that be achieved if we use essentially the same knowledge and resources?

Infusing lessons with Black perspectives is not a minor epistemic move. Carter G. Woodson, originator of what we now call Black History Month, knew this:

Woodson understood that what was taught had to challenge the existing ideas, theories, histories, and silences that existed in the traditional schooling context. Thus the teaching of Black history and the cultural, political, creative accomplishments of African Americans was vital for changing the ontological meanings of Blackness that were pervasive in schools and society. (Black Intellectual Thought in Education, p. 106)

Learning Black history has been reduced to identifying Black people who were the first of the race to accomplish a particular achievement. Even more prominent Black people are primarily characterized by a quote or an excerpt from some intellectual contribution or notable moment; rather than a systemic analysis of their larger body of work. They are presented as frozen in time and static in their perspectives, often the multifaceted knowledge they disseminated is forsaken for a singular topic. Thus, infusing Black perspectives is about taking Black people seriously as intellectual contributors and using their intellectual production to educate future engineers. One resource to help with this is Black Intellectual Thought in Education, a book about Black educational theorists we can draw upon to shape our teaching practices and philosophies. While this example is about educational theory, we can also study practitioners within our respective disciplines to introduce students to conceptual knowledge produced by Black professionals when teaching core course content. At my institution I have helped design lectures using information about Elijah McCoy’s automatic lubrication system. These modules have been taught in two of our core mechanical engineering courses: Introduction to Solid Mechanics and Modeling, Analysis, and Control of Dynamic Systems.

James Holly, Jr. with University of Michigan faculty, staff, students, and local community members visiting the Starkweather Homestead, located in Ypsilanti, MI, a stop on the Underground Railroad. James organized this trip as a co-lead of The Sankofa Project.

I believe shifting the pedagogical norms of core engineering courses is essential for transformation to occur. I also believe we need a multi-pronged strategy to extend the capacity of this work. In this vein I teach an elective mechanical engineering course for graduate and undergraduate students entitled Mechanical Engineering and Racial Justice. In this course I implement strategy #2, including texts by Black authors. One of the texts we discuss is Fatal Invention, which disabuses notions that race has any biological basis and helps students grasp the political functions of race. Moreover, I invite Black guest speakers, some of whom are engineers and others who are community members. By primarily using scholarship from Black thinkers, activists, and professionals to counter deficit notions of Black intellectualism, this approach to teaching engineering helps students to acknowledge, understand, and counteract the ways engineering knowledge and practice have been rooted in White supremacist epistemologies. Using text by Black authors expose students to different ways of knowing and writing, functioning as an epistemic resource to achieve the course learning outcomes: (i) explore the social, political, environmental, and historical context of engineering, (ii) engage in critical inquiry into the assumptions and practice of mechanical engineering, and (iii) initiate the development of an alternative culture and practice of mechanical engineering that is racially just.

Doing the work

Of the aforementioned fugitive pedagogy methods, my favorite is #3. Despite our best intentions, engineering classrooms remain fraught with mistrust and hostility between faculty and students, particularly as a Black professor. Extracurricular spaces provide flexibility to educate in non-traditional ways; furthermore, they supersede the constraints of school curricula to comprehensively counteract epistemic oppression. Beyond the academy’s resistance to change, the epistemological resilience of anti-Blackness requires curricular revision to be both outside and in-concert with traditional academic spaces. Again, this is not a new concept. The authors of Black intellectual Thought in Education explain this Woodsonian approach means “recognizing the limitations of the curriculum choices that are made available to historically underserved groups and then pursuing a comprehensive counter-hegemony project from the academy to the classroom” (p. 104).

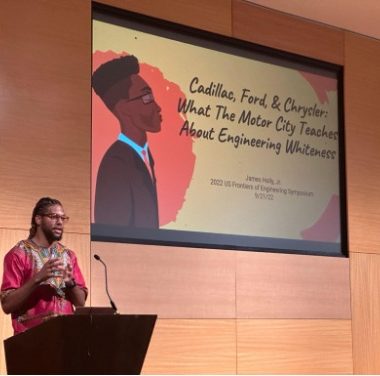

James Holly Jr. presenting at The Grainger Foundation US Frontiers of Engineering Symposium

I facilitate extracurricular education through an initiative I co-lead entitled The Sankofa Project: Cultivating Socially Conscious Engineers. The purpose of The Sankofa Project is to use Black history as a guiding resource for re-engineering a more humanistic future. Black history is often told in public discourse with a deficit orientation, which can leave Black students feeling ashamed, and with many inaccuracies, which leaves all students miseducated about the origins and trajectory of our current social reality. In pursuit of making equity-centered engineering real, we believe we must first identify and understand the mechanisms that have constructed the inequities engineering perpetuates before we can redress them and remake new ways of being, thinking, and doing. Toward that end, we host field trips and educational socials to generate critical discourse, rather than lecturing, with students to help them consider the ways technical knowledge is entangled with social implications. Our activities have included: visiting one of the world’s oldest independent Black cultural museums, taking a tour of local sites that were part of the Underground Railroad, hosting panels for Black students to give tips on how the broader educational community can support them, and media nights to discuss sociotechnical documentaries (e.g., cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo). This project aims to restore accuracy and strength to the narrative about Black Americans’ role in developing our country, but that’s just the entry point. We then use facilitated discussions to inquire about connections students notice to mechanical engineering in the stories and events they learn about, and prompt speculation about how they/we can contribute to changing the material and social conditions for Black Americans and others disenfranchised within our society.

This work is difficult, but it is necessary. And in case you’re wondering, yes it has gotten me in some trouble in spite of the verbal affirmations I have been blessed to receive. I share these illustrations of my pedagogical activities not as exemplars, but to demonstrate this work is feasible. Much of the recent engineering education scholarship I’ve read suggests the time is ripe for a movement toward educational equity. I’m just looking for some more folks willing to get in some “necessary trouble.”

About the Author

Ɔbenfo James Holly, Jr. (he/him/yeye) is an Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering and core faculty member within the Engineering Education Research program at the University of Michigan. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Tuskegee University and a master’s degree from Michigan State University, both in Mechanical Engineering. He earned his doctorate in Engineering Education from Purdue University. His research paradigm is shaped by his experiences growing up in a Black church within a Black city and later studying engineering at Tuskegee University, a Black institution, three spaces where Blackness is both normal and esteemed. His scholarship focuses on the ways disciplinary knowledge (i.e., mechanical engineering) reinforces racialized power, the role of culture and cognition in teaching and learning, and preparing pre-college engineering educators to identify and counteract racial inequity. He directs the Enkofa Research Village, a research group whose focus is to esteem the heritage knowledge of Black engineering students, faculty, and researchers, along with nourishing their self-knowledge; also, to support non-Black scholars committed to accomplishing racial justice in engineering.

James is the Co-founder, Past Program Chair (’20) and Division Chair (’21) of the Equity, Culture, and Social Justice in Education Division (ECSJ) of ASEE.

LinkedIn – https://www.linkedin.com/in/jhollyjr

Do you want to become a guest blogger?

CDEI Guest Blog highlight future events, describe best practices, or share calls to action by CDEI members. We invite you to propose posts that share brief research highlights, reports of impactful initiatives, critical thought pieces, and resources you find useful. We especially encourage emerging scholars to share their work. If you are interested in sharing a blog or resource post, you may submit your proposal here. All posts are screened and edited.